Presente Infinito, Rubbettino editore, 2023

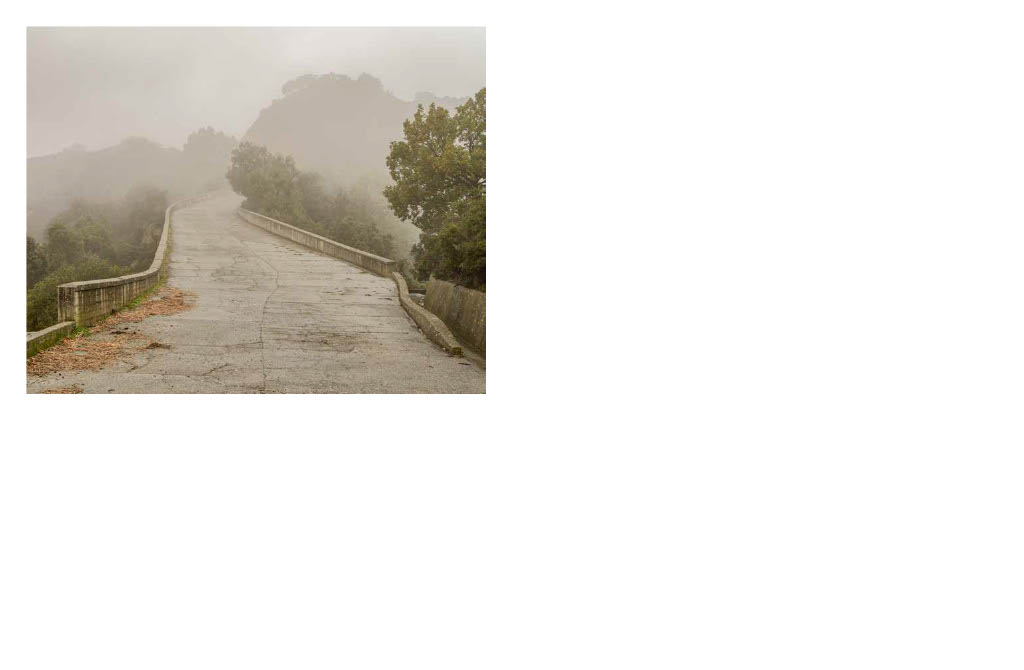

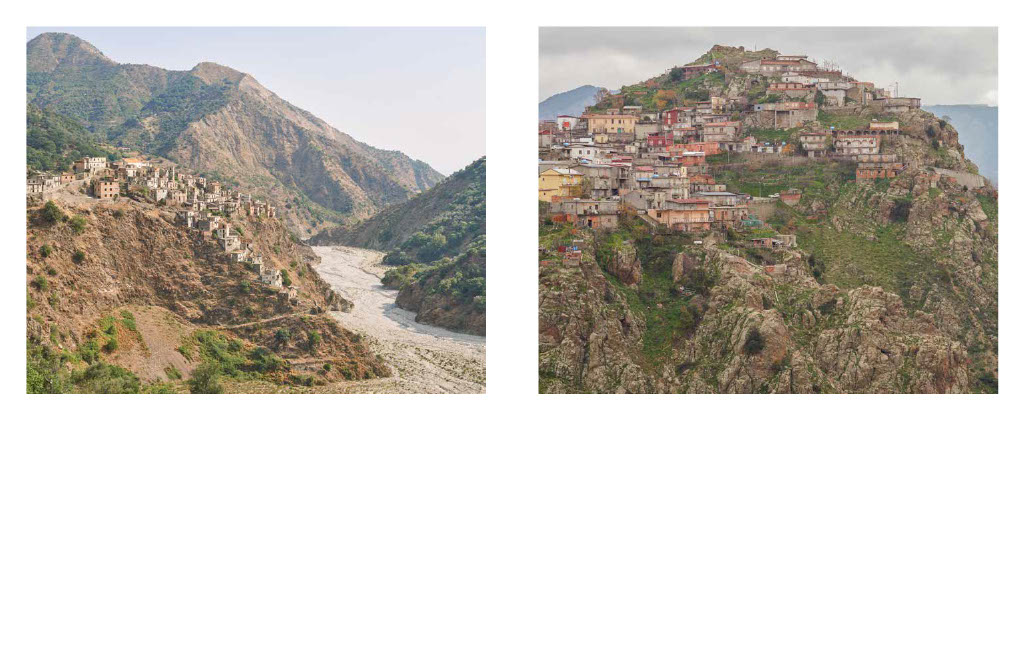

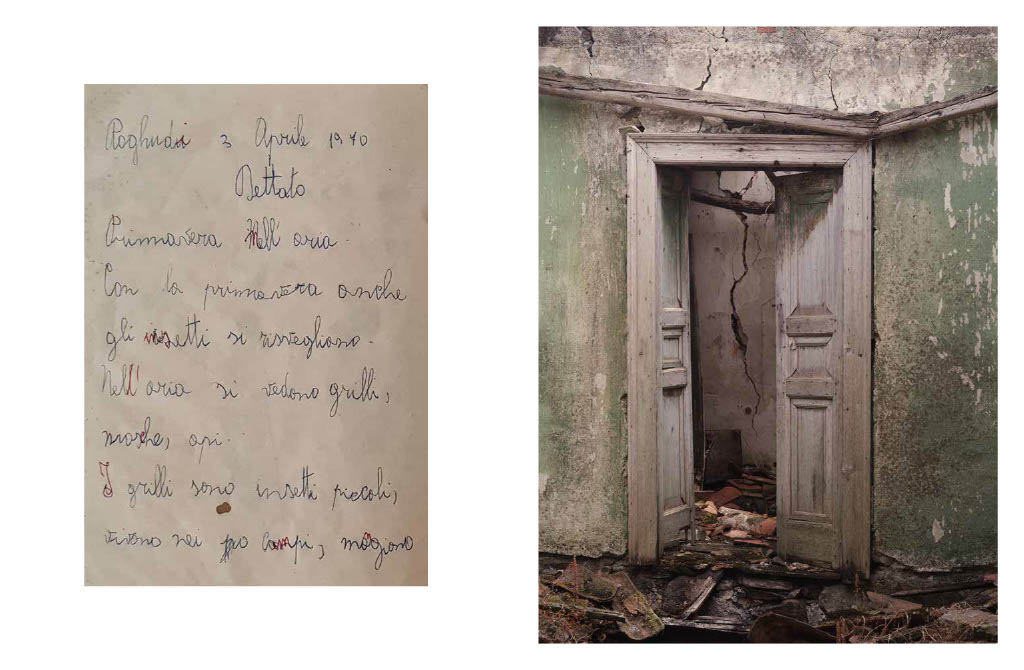

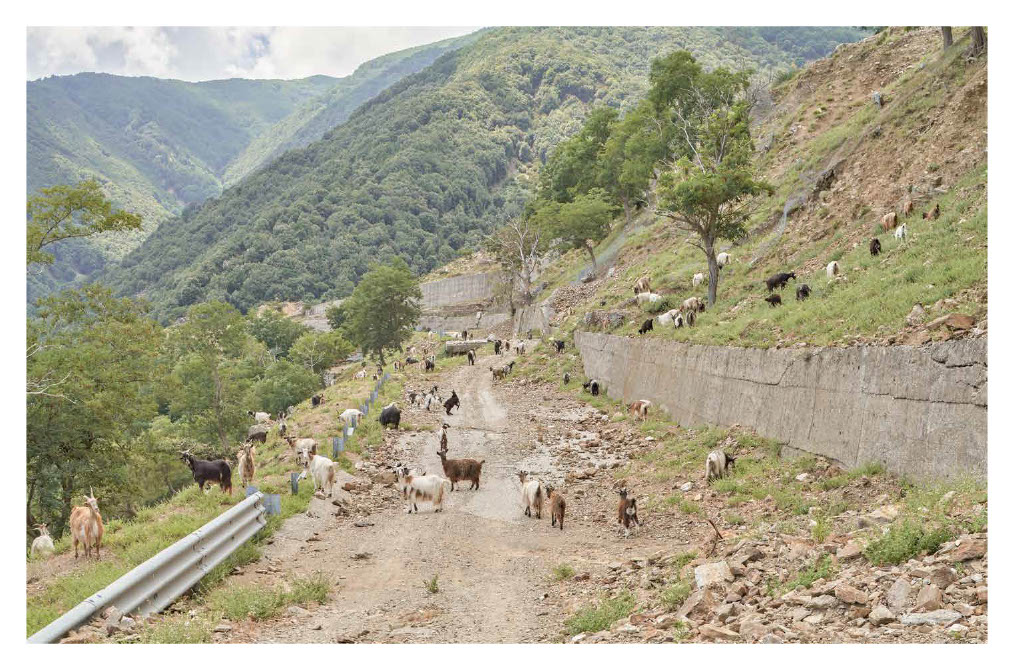

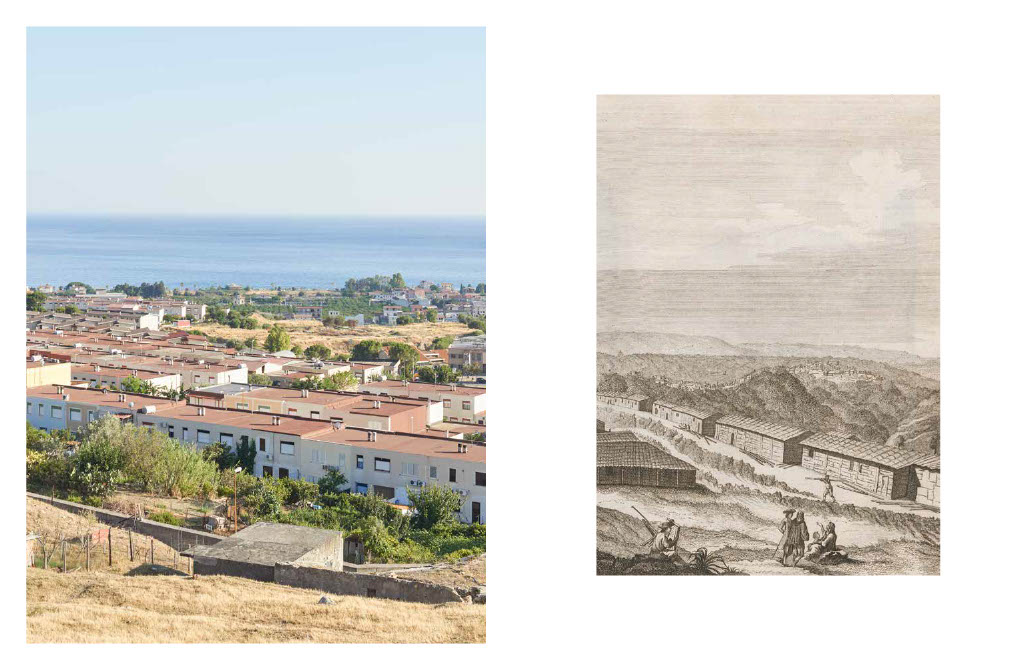

The inner Landscape. The historian Augusto Placanica describes the peculiar relationship between man and environment in Calabria by resorting to the figure of the "inner landscape", defined as "a meeting point between two territories, that of the soil of Calabria and that of the soul of the Calabrian—a place where the history of the territory and the landscape, of architecture and culture, of lifestyles and of the soul, merge".

Without doubt, this definition recalls the traditional definition of "landscape", understood as a set of intelligible signs, traces of man on the territory which, as part of a discourse, tell us about the ensemble of relationships that form the bond between man and nature. And yet, the peculiar events that have accompanied the evolution of Calabrian communities—trapped in a very long parenthesis of absolute isolation, from the end of the Magna Graecia civilization until the contemporary era—which have led to a crystallization of socio-economic and socio-cultural structures, allow us to imagine that the normal nexus of conditioning between man and environment has deepened to the point of generating even a fusion or identification between the human element and the natural one.

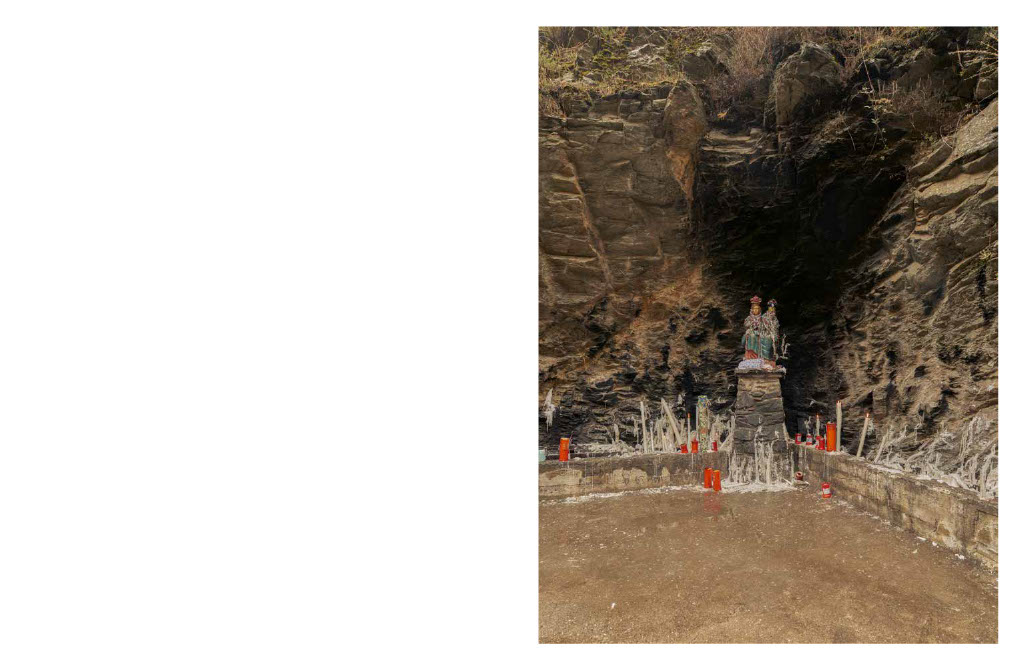

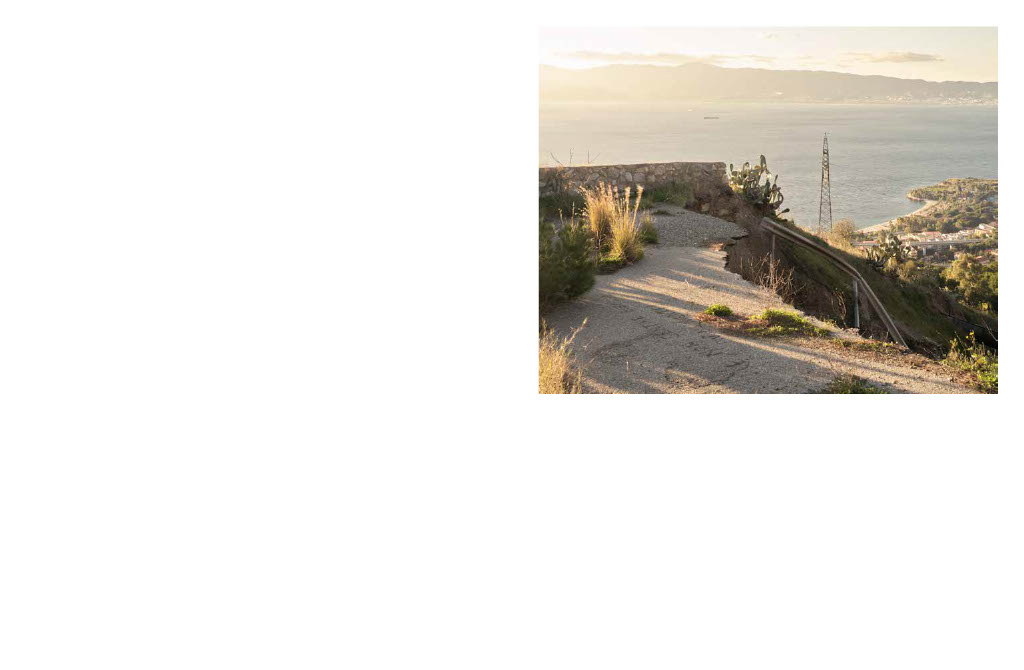

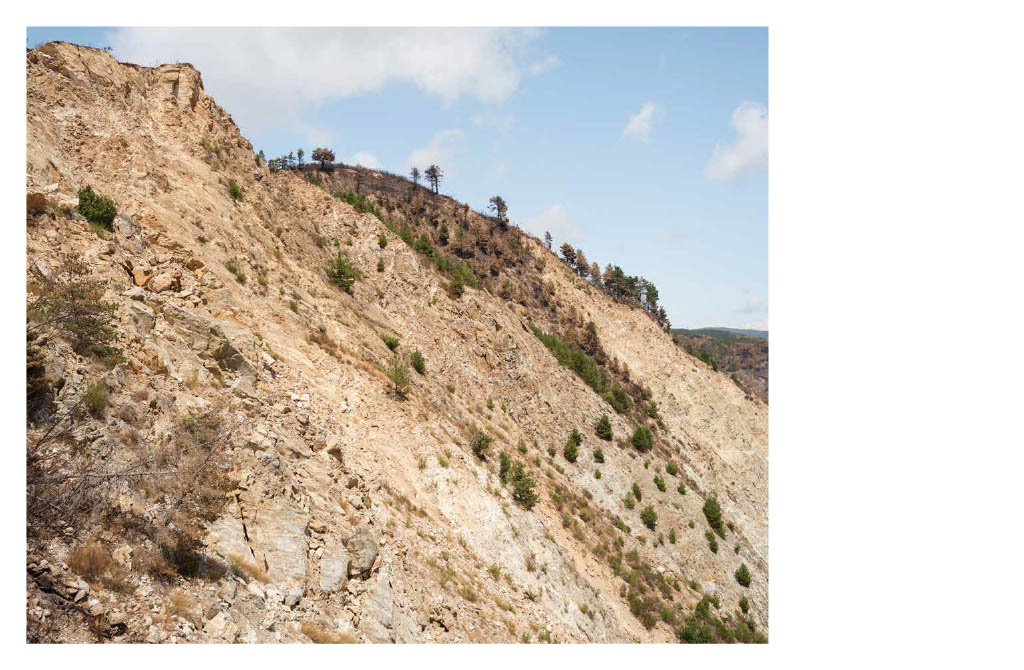

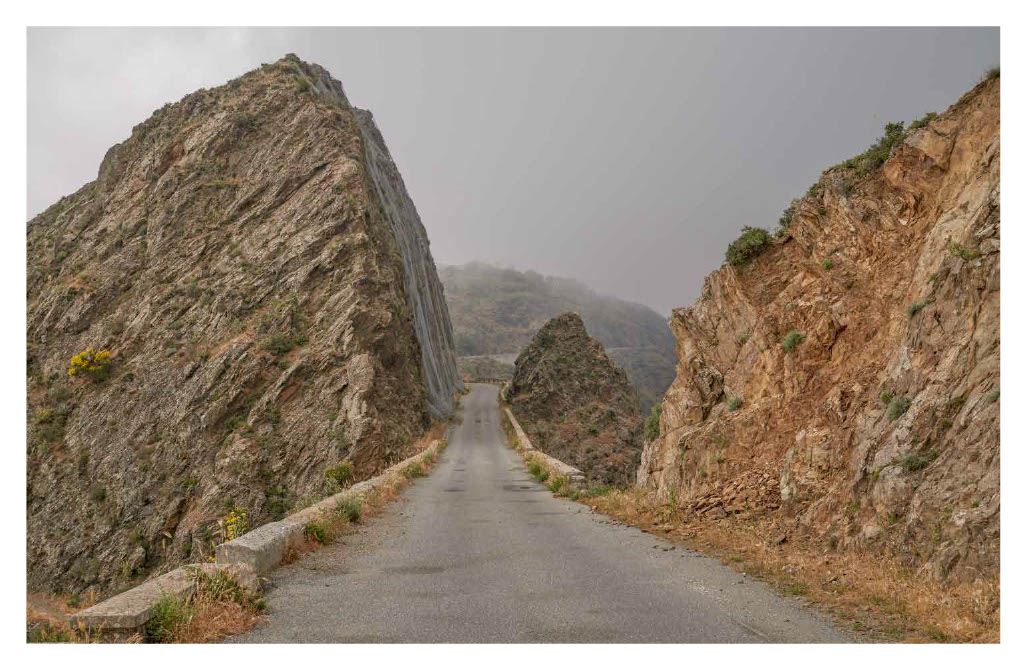

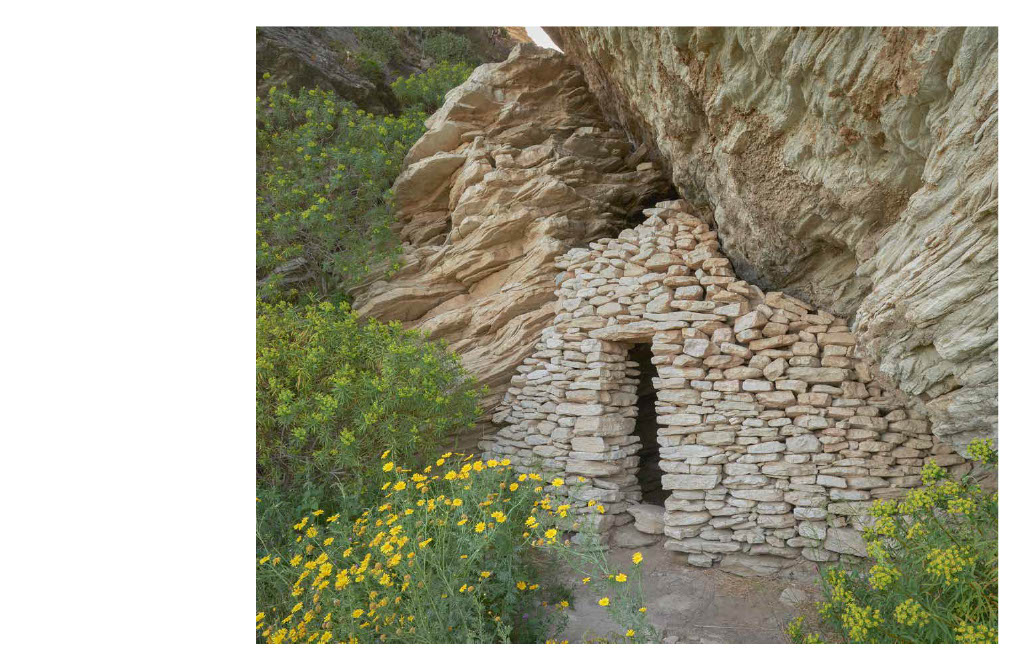

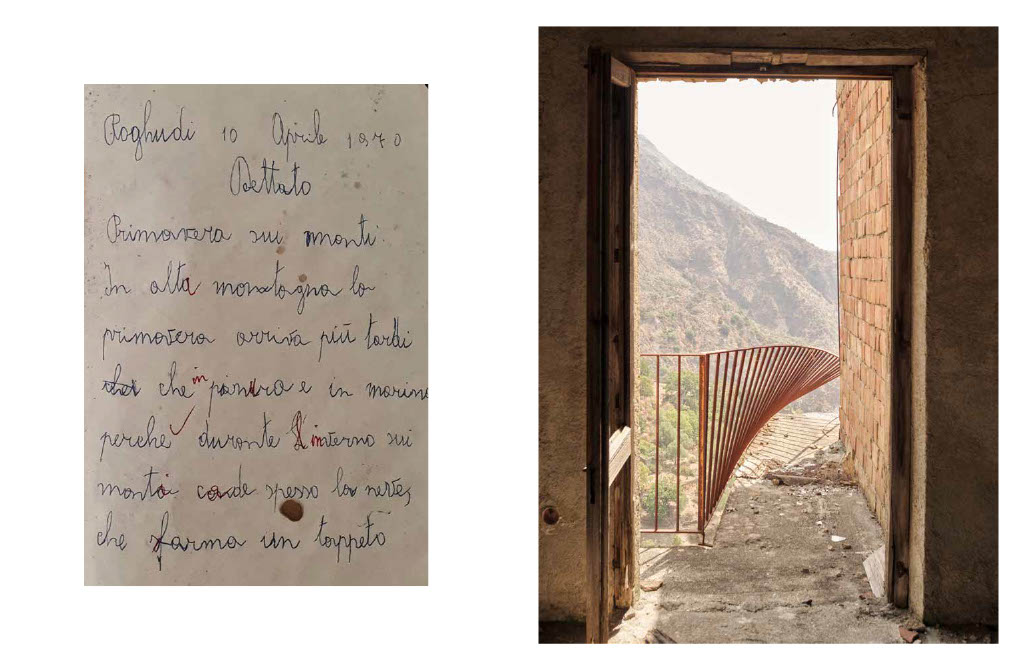

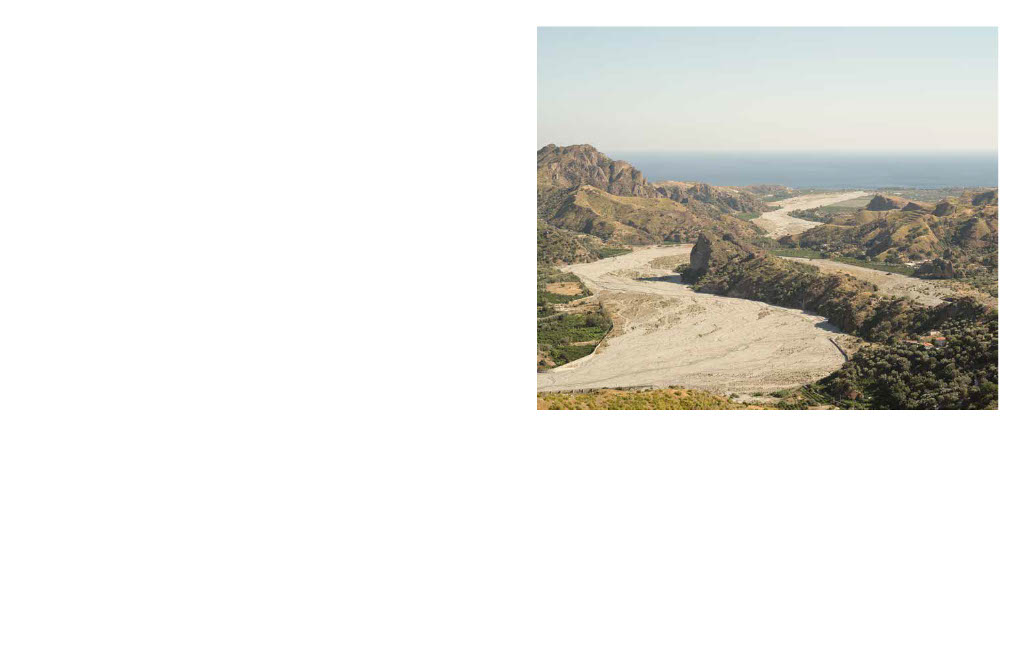

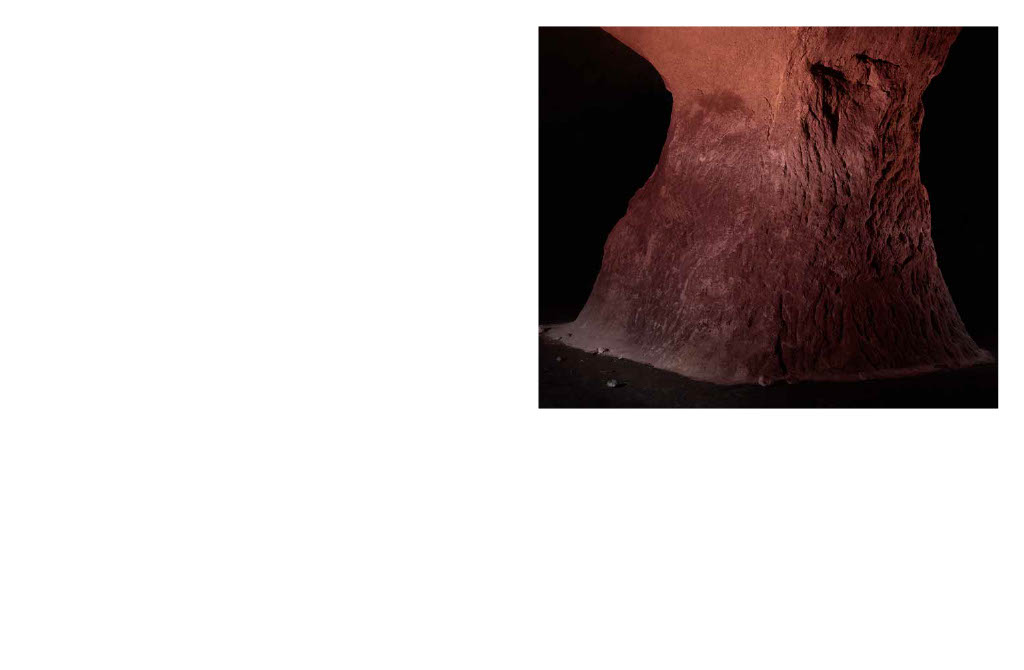

To navigate within this "landscape", it is necessary first and foremost to free oneself from any spatial and temporal coordinates, in order to grasp the symbolic essence of the relationship between man and nature. And it is no coincidence that the archetypal element of this landscape is constituted by stone, by bare rock, which over the centuries has provided refuge to monks and hermits who, fleeing from anti-Christian persecutions, left behind the things of this world to abandon themselves to an ancestral relationship of fusion with the natural element.

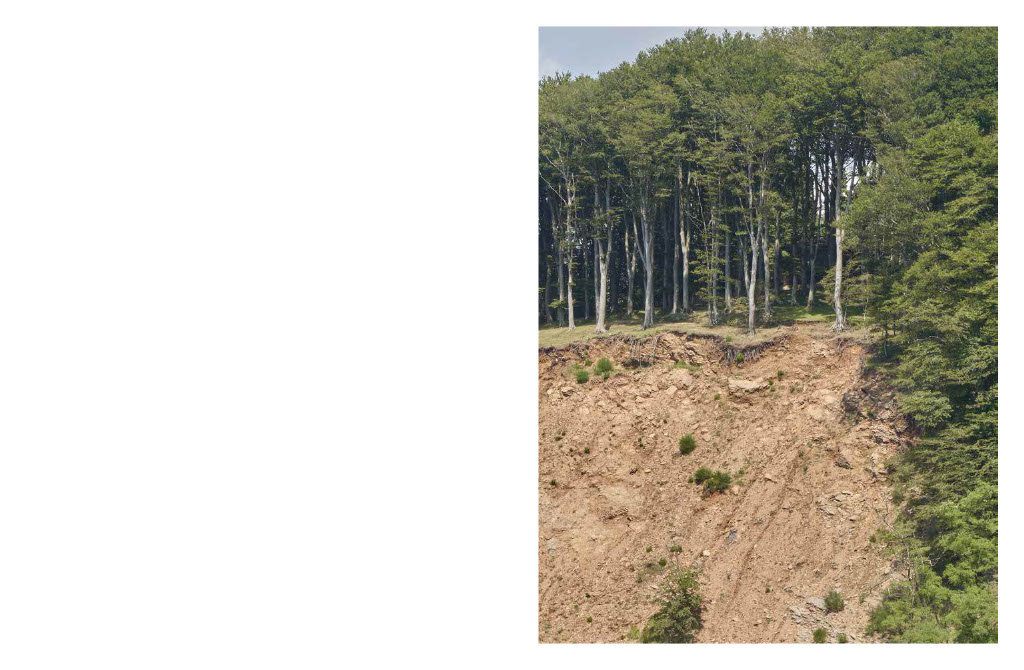

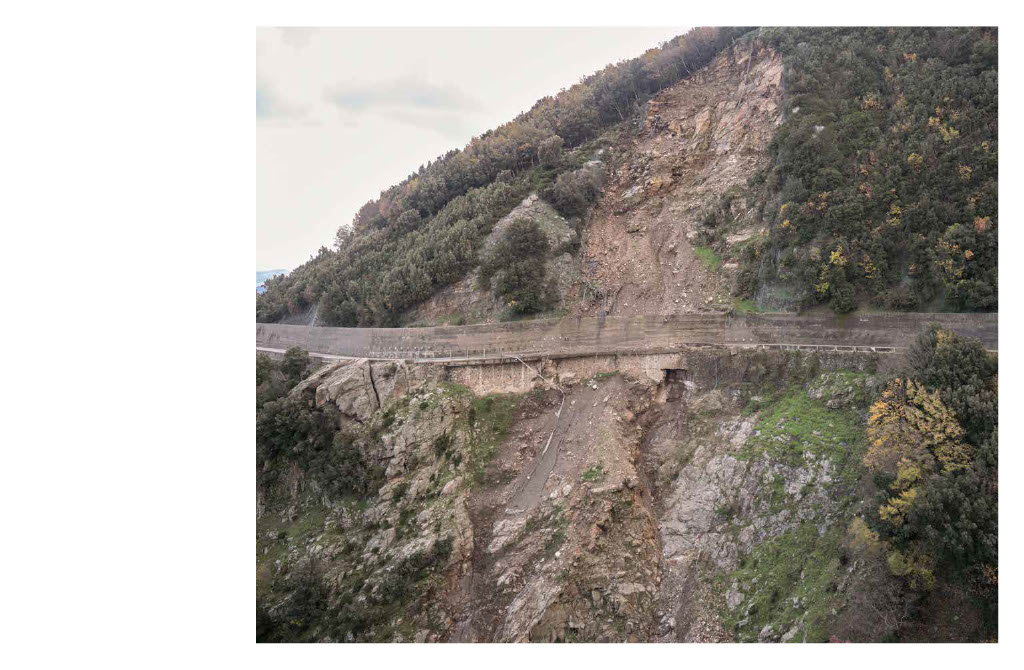

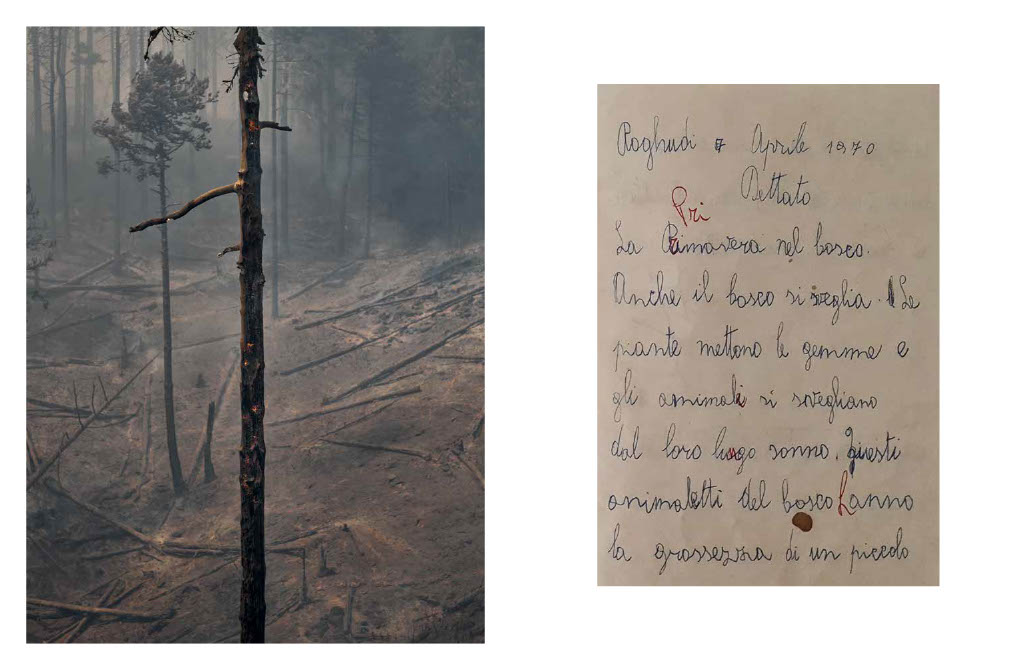

This landscape finds its identity under the sign of trauma, of crisis, since over the centuries earthquakes, landslides, and floods have constantly punctuated the relationship between man and environment, conditioning the evolution of communities to the point of fostering the emergence of a disillusioned view of life among the affected populations.

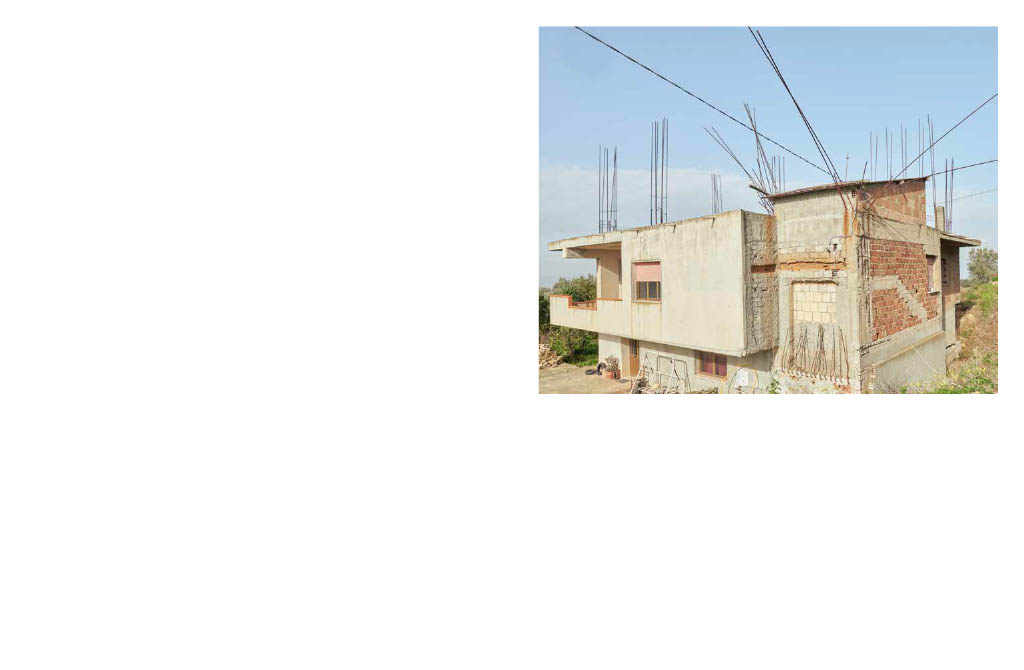

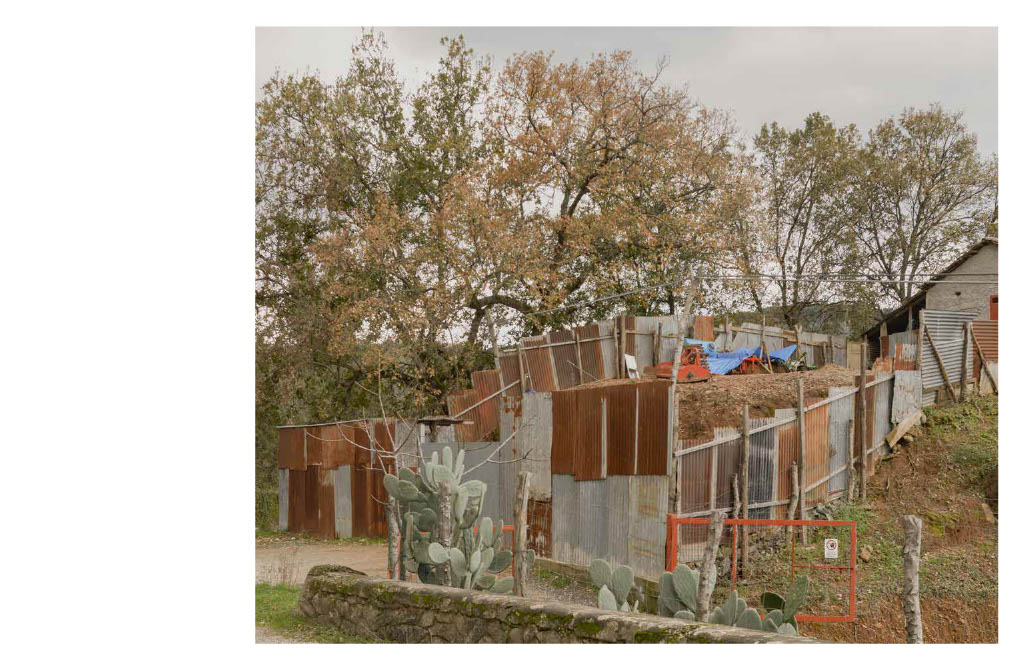

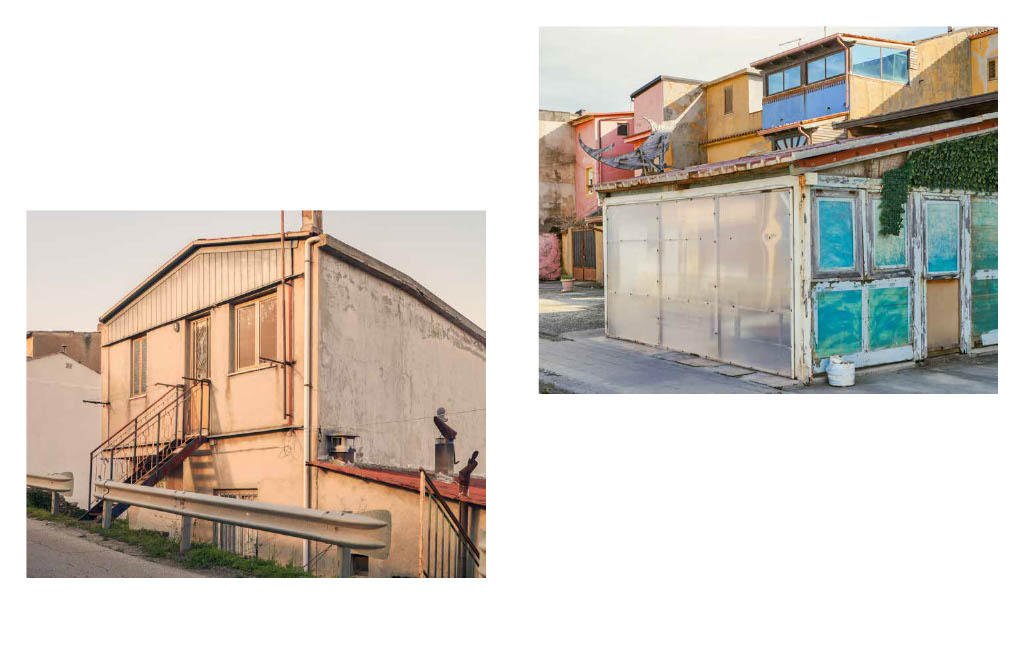

The Calabrian landscape must therefore be framed in its fragility and precariousness. And here, in the perspective of a fusion between the human and natural elements, the constitutional weakness of the terrain corresponds to the weakness of the economy, of settlements, and of building structures. This vision refers us to a humanity squeezed in the grip of natural requirements, confined to the limited horizon of the present.

The Infinite Present. "Candido, o l'ottimismo" is a philosophical novel by Voltaire in which the Lisbon earthquake of 1755, considered one of the most destructive in history, serves as an occasion for the protagonists, Candide and his tutor Pangloss, to embark on a journey of formation that will prove to be studded with an impressive series of catastrophic events.

These events confront Candide and Pangloss with the most decisive of questions: Si deus est, unde malum?, that is, the necessity of reconciling the evil that man inevitably encounters along his path with the fundamental goodness of God. Called upon to attempt a synthesis is Pangloss, who for this purpose resorts to Leibniz's theory of the "Best of all possible worlds".

According to this interpretation, God would allow evil in the world in as much as it would always be balanced by a superior Good, a balance knowable only to God and inscrutable to man.

However, Pangloss becomes an advocate of a mechanical and rather obtuse interpretation of this theory, as he pretends to seek, for every catastrophic event encountered along the way, an immediate balance, empirically measurable in reality, and such as to bring the "balance" between good and evil back into the positive. It is obvious, however, that if one must speak of balance, the latter goes beyond man's understanding, and consequently cannot be reduced to a vulgar utilitarian calculation.

This theory leaves Candide quite perplexed, allowing Voltaire, in this way, to introduce through him the theme of distrust toward any providential and transcendent design, which characterizes the Enlightenment vision.

The work thus closes with Candide's wish that everyone strive to "cultivate their own garden".

It is true that the invitation to "cultivate one's own garden" is framed by Voltaire in an "anti-metaphysical" dimension, which translates into the necessity for man to attend to the concrete, immanent dimension of existence. However, I have always thought that Candide's maxim could in a certain sense be open to a further specification of meaning.

"Infinite Present", from this point of view, represents the attempt, through a path of personal research, to find this meaning.

It is a genealogical path: a backward journey oriented toward the original, primordial dimension of the relationship between man and Nature, already addressed in its literal and descriptive dimension in the first level of reading of the project.

Tarkovsky, distinguishing the "principle of poetic logic" from "literary logic", describes the artist's vision as one capable of perceiving "the poetic organization of existence", "of transcending the limits of formal logic to express the particular nature of the subtle bonds and profound phenomena of life, its profound complexity and truth" (A. Tarkovsky, Scolpire il Tempo, 2015).

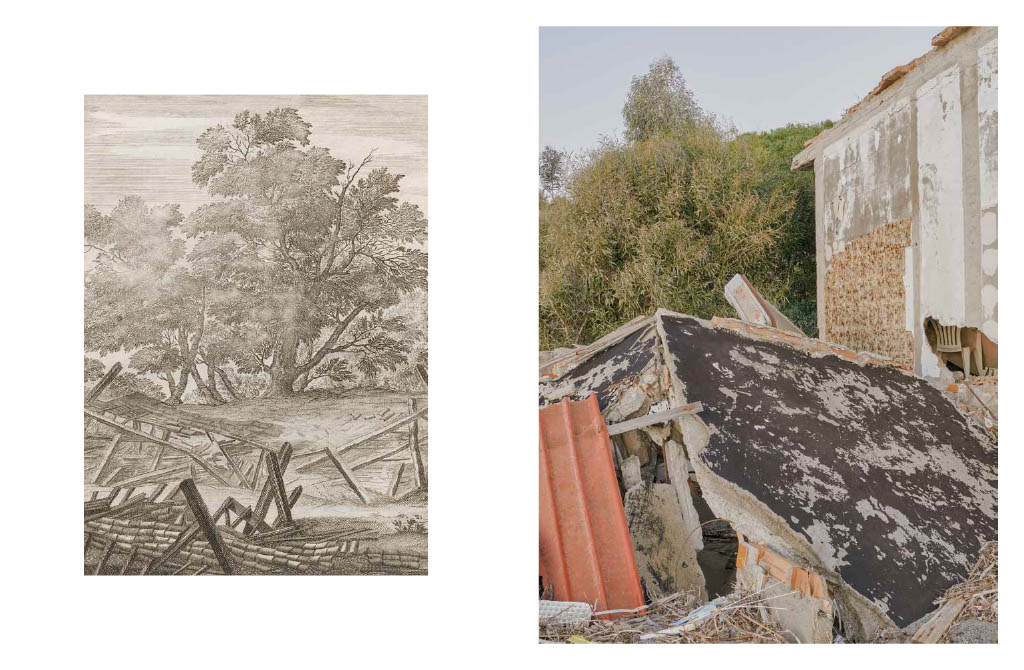

"Poetics" (ποίησις), as the essence of every artistic manifestation, is a process of knowledge, of searching for "truth", "which wants to get to the bottom of things" (Filaninno Indelicato, Per una filosofia del tragico, 2019) and which, centered on an activity of mimesis (μίμησις)—imitation—, as "representation of representation", goes beyond the mere naturalistic recording of phenomena, to open up to allegorical narrative and the image in its symbolic dimension.

Thus, representation understood as "something that stands in place of something else", which "embodies" it, instead of identifying with it.

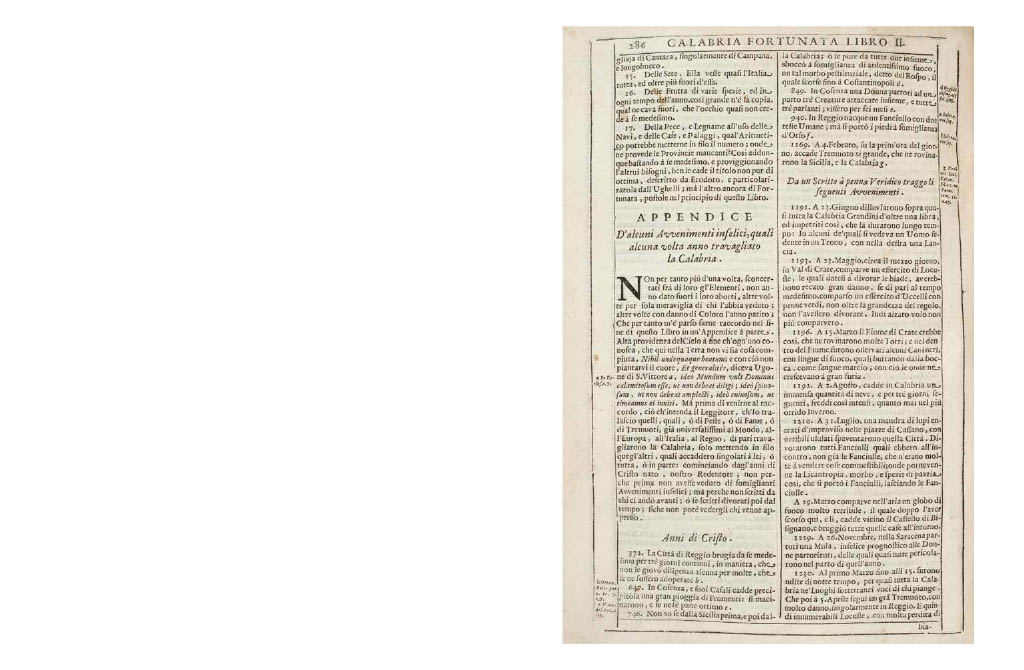

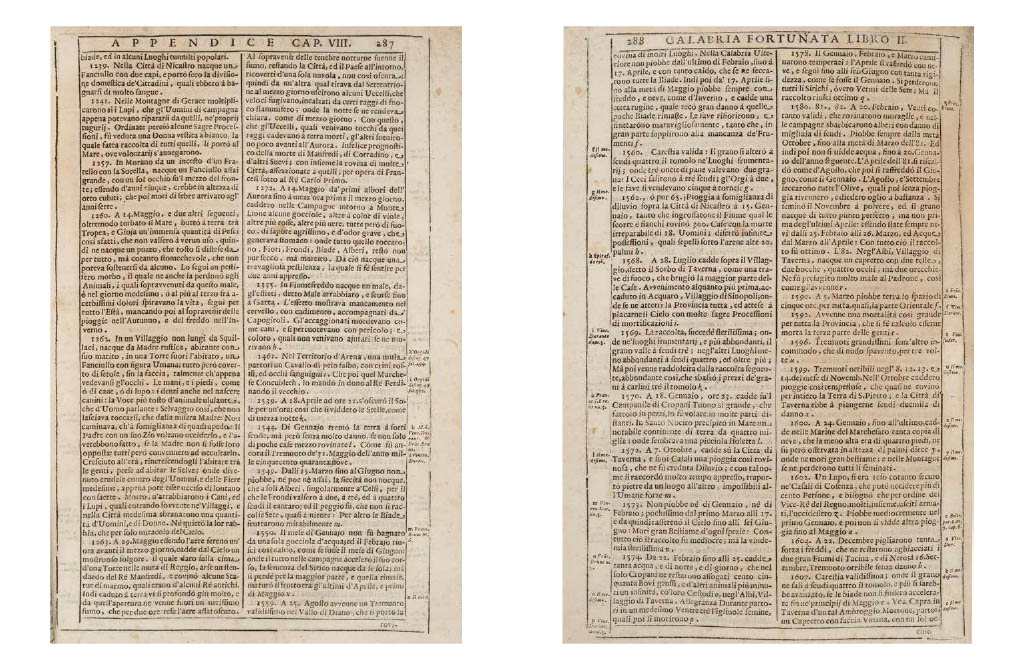

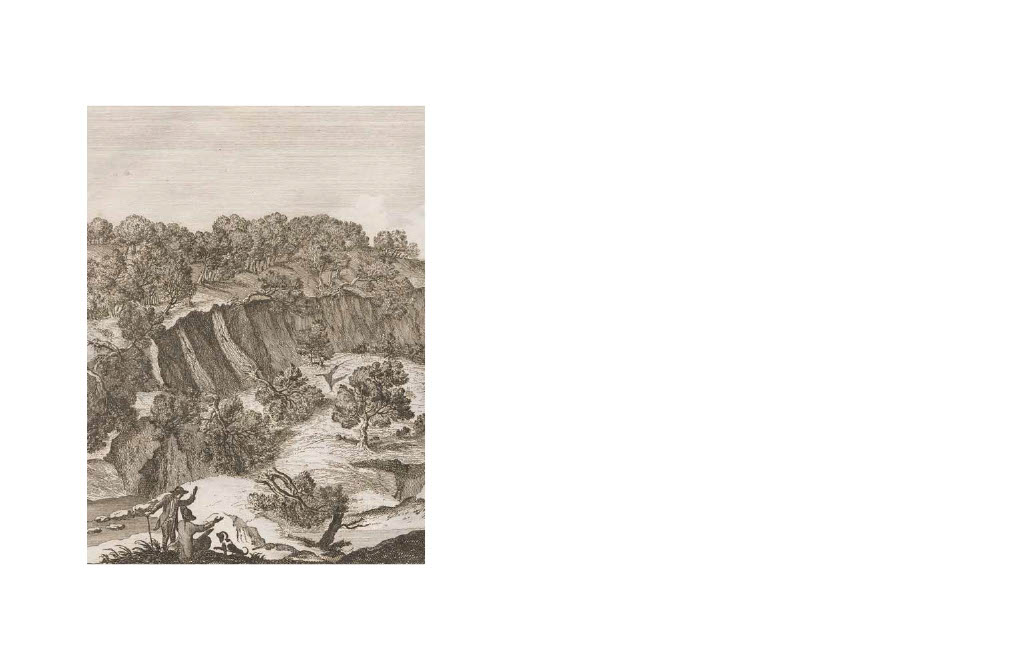

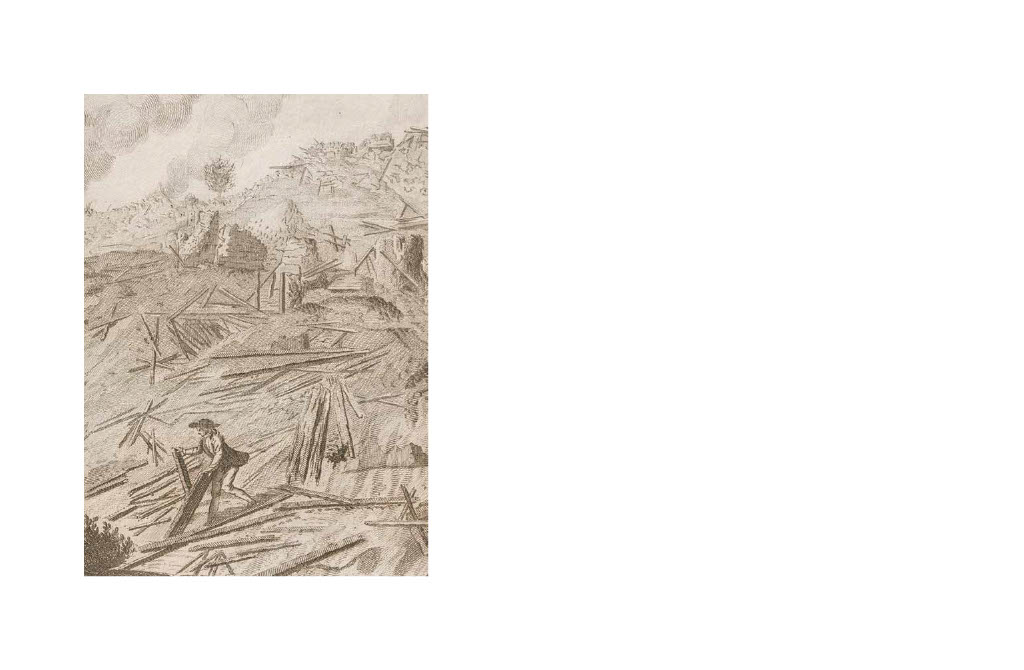

The chapter "D'alcuni avvenimenti infelici quali alcuna volta anno travagliato la Calabria", an appendix to the work "Della Calabria Illustrata" by Father Giovanni Fiore da Cropani, reproduced in anastatic copy as an introduction to the photographic project, serves precisely to project the narrative into this allegorical dimension to which I have just alluded. The chapter reports a numerous series of catastrophic events, ordered chronologically starting from 372 A.D., which, in their imaginative and grotesque content, recounting plagues, incests, and monstrous creatures, in a certain sense fulfills the function that the events narrated by Voltaire perform in Candide: to transpose the narrative from the descriptive and literal plane to the allegorical and symbolic one.

"Those men have lived too long in the grip of natural requirements, and they had neither sufficient energy, nor guides, nor occasions, nor means, to push beyond their limited horizon: forced to flatten themselves onto an infinite present to defend with all their strength, the individuals lacked, and the community lacked, the taste for looking and providing for a higher tomorrow" (A. Placanica, Storia della Calabria, dall'antichità ai giorni nostri, 1994).

At the bottom is the relationship between man and Nature: an antinomic relationship, based on man's ability to fight strenuously against adverse events that can occur outside his will. And life, understood in its indissoluble bond with the ineluctable, with necessity, "ananke" (ἀνάγκη), which constitutes the foundation of the tragic dimension of existence understood as a philosophical idea.

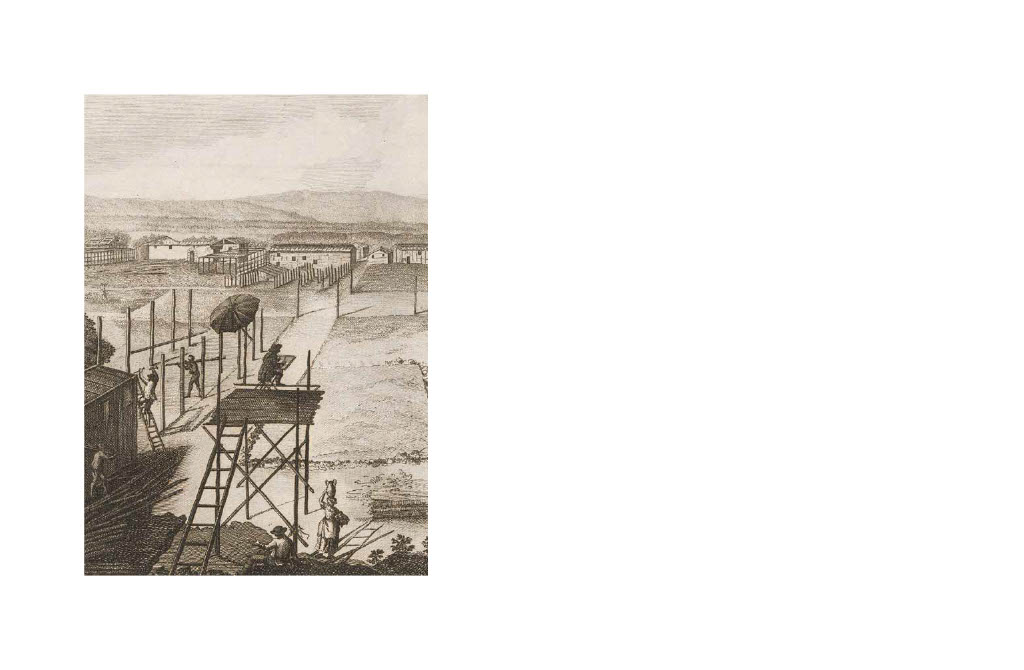

The volume "Il Filosofo e la Catastrofe, un terremoto del '700" (A. Placanica, 1985) collects the testimonies of the missions that, in the aftermath of the 1783 earthquake, were sent by the Kingdom of Naples to offer assistance to the affected populations.

The widespread interpretation in these accounts is that man, faced with traumas of this magnitude, undergoes a process of regression toward a pre-logical and pre-moral condition: he, stripped of any social conditioning, shows himself in a condition of "natural nudity". Consequently, he loses every inhibitory restraint, abandoning himself, for example, to promiscuous sexual behaviors.

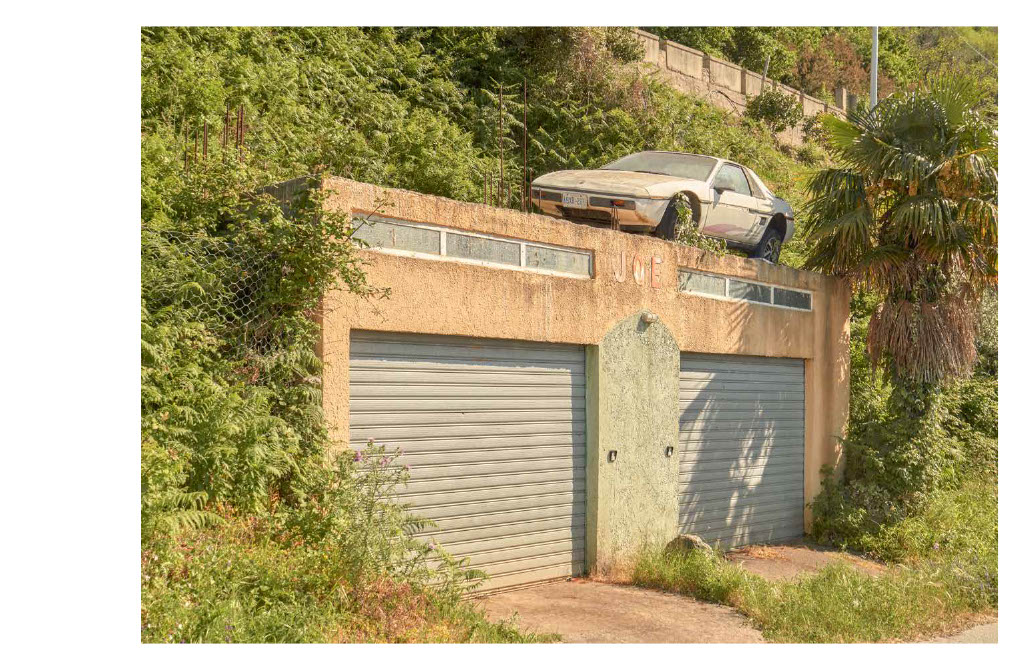

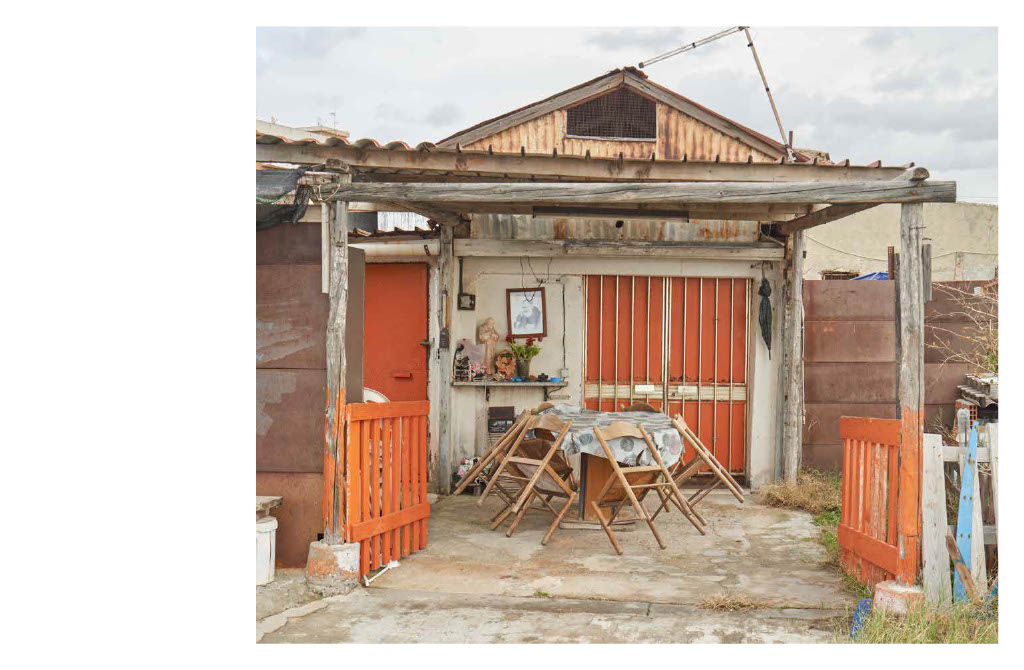

The trauma represented in "Presente Infinito", however, does not reveal itself in its dimension as a disruptive event, a "scourge", capable of temporarily demolishing the social superstructures of a community. The dimension of temporal dilation is in fact fundamental to define the relationship between man and Nature and consequently man's attitude toward "necessity".

The trauma, when it is a constant presence, becomes capable of permanently affecting the attitude toward life within a given community; and the magnitude of such influence is encapsulated precisely in the definition "infinito presente" coined by Placanica. Man is essentially overwhelmed, defeated, in this unequal clash with superior forces, to the point of having to concentrate his energies toward satisfying the primary needs of the present, consequently losing the possibility of looking toward a broader horizon.

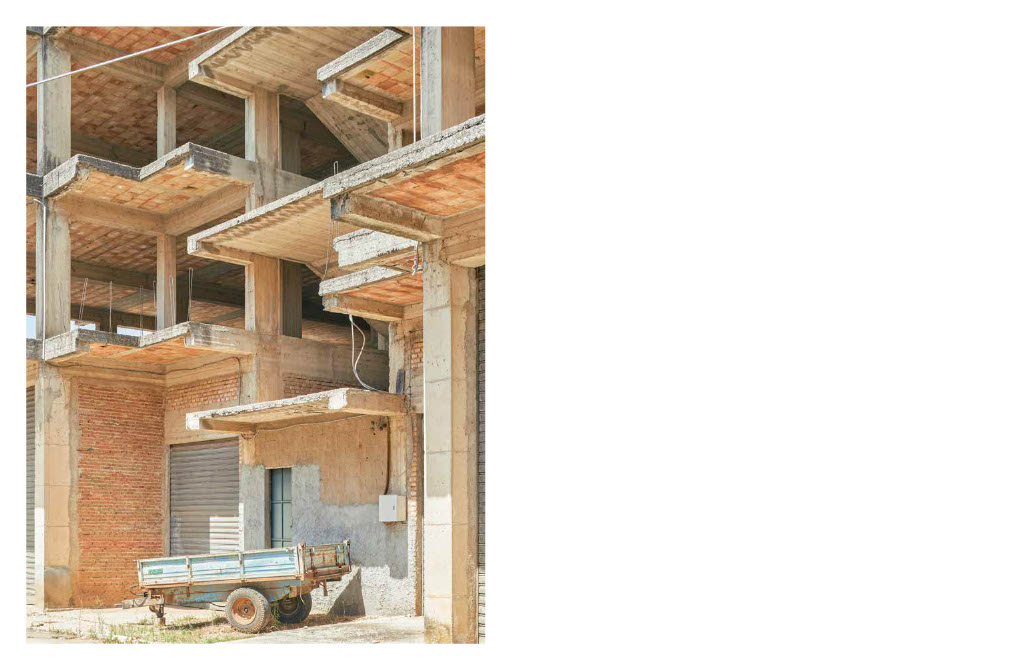

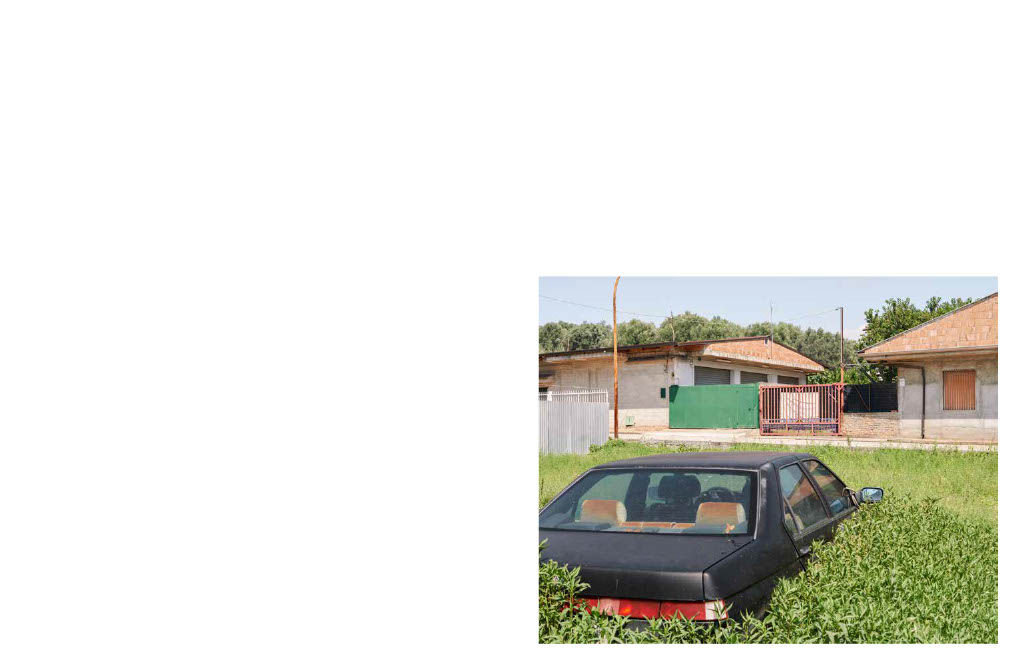

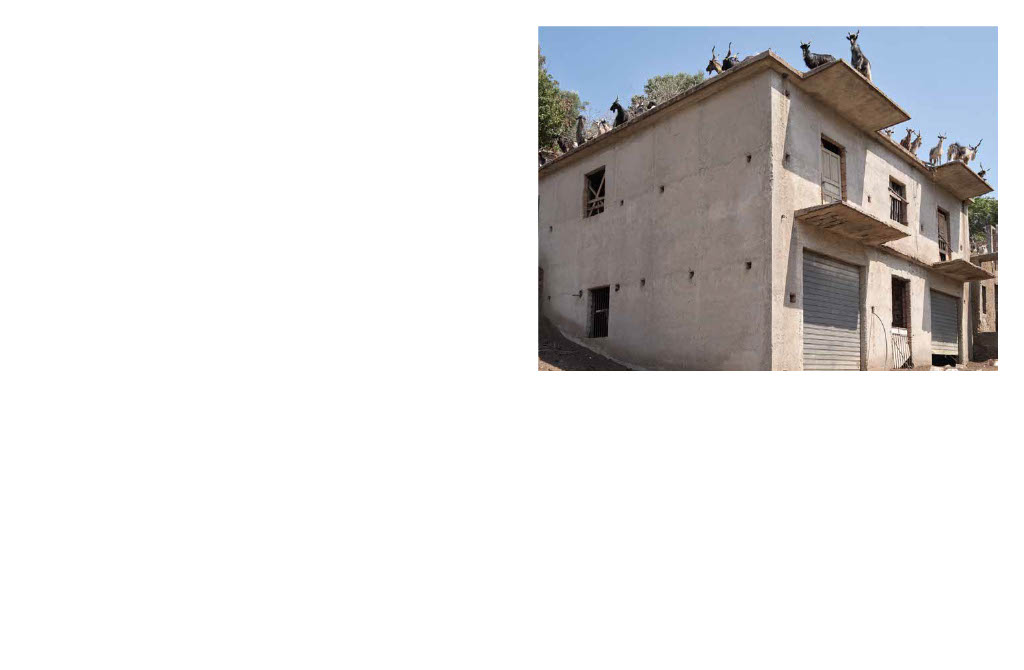

Placed in this perspective, man's works, far from representing ruins or, worse, being symbols of degradation or abandonment, represent the phenomenal dimension on which this confrontation between man and nature unfolds: they are its most tangible translation. Their character as "unfinished", the precariousness of forms and materials, are testimony to this tension.

The "divorce" between man and the world is defined by Camus as the "sense of the absurd". And the "absurd man" is he who moves with this awareness, "he who, without denying it, does nothing for the eternal".

The archetypal character of the absurd man is Sisyphus, condemned by the gods to a hopeless labor: rolling a boulder to the top of a mountain, only to see the stone fall back due to its own weight. After seeing the stone plummet, in the descent, his tragic destiny is fulfilled:

"I see that man descending with a heavy but even step toward the torment, of which he will not know the end. This hour, which is like a breath, and which recurs with the same certainty as his misfortune, this hour is that of consciousness. In each instant, during which he leaves the summit and gradually immerses himself in the caverns of the gods, he is superior to his own destiny. He is stronger than his boulder" (A. Camus, Il Mito di Sisifo, 1942).